The Ireland of the eighteenth century that saw the development of setters had a different landscape to that of today. Picture, if you will, Ireland without coniferous plantations, without mechanised peat extraction or artificial drainage, and you will see a land of wide horizons and great expanses of heather – a land of mountain and bog. The vast expanses of heather were the home of red grouse, snipe and woodcock, while the better land supported a decent stock of grey partridge and some introduced pheasants. With the advent of firearms, Ireland was a paradise for the hunter and, although game was never over-abundant, there was certainly sufficient to attract the attention of those who enjoyed the pleasures of hunting with dogs in a wild and beautiful countryside and where variety took the place of huge bags. The interaction of landscape, game and breeders developed the two setter breeds that are native to Ireland.

Little is known of the origin of the Irish red setter.’ Without doubt, both the Irish red setter and the Irish red and white setter are descended from the land spaniel and were referred to, in parts of the country, until quite late in the last century as spaniels. The red and white setter was in existence prior to the red setter. The crosses that were used to produce the whole red setter are unknown and there are no defined sources other than prints and paintings that give information on the transition. It is clear that both red setters and red and whites were interbred and were considered as one race in the eighteenth century. A tendency to throw black individuals persisted for some time and was eventually bred out. At a guess, this tendency is probably connected to efforts to produce a self-coloured red dog, as breeders of the day must have used an outcross to a solid-coloured dog.

It is interesting to note the similarities between some of the breeds that were being developed at that time. The Welsh springer spaniel, the Brittany spaniel and the Irish red and white setter all have similar colouring and markings. All have land spaniel origins, despite the fact that their conformation now varies considerably. That all these dogs remained gun dogs displays the strength of their working origins and the differences in their conformation are a manifestation of their evolution for working in different environments.

Proof that they were efficient at their job is given by Richard Badham Thornhill, who wrote in his Shooting Directory in 1804: “There is not a country in Europe that can boast finer setters than Ireland.”

Why or when the Irish red and white setter and the Irish red setter became separate is not apparent from early literature. The developments that led to this have been discussed by many observers of the breed and the most sensible of these argues that red dogs, distinguished by particular excellence, were used extensively at stud and thereafter the solid red colour became a hallmark of excellence and was selected for in preference to the red and white in their subsequent progeny.

The crosses that produced the solid red dog are unknown, but it should be borne in mind that most of the Irish native breeds are solid coloured. The Irish wolfhound, the Irish water spaniel, the Irish terrier and the Kerry blue terrier are all examples. This may have been particularly relevant, in that one of the similar-sized breeds may have been used in the development of the solid-coloured dog. It is worth remembering that many of the best working Irish red setters still show a strong tendency to throw some white on the head, chest, feet and tip of the tail and this fact was written into the breed standard which remains the same today.

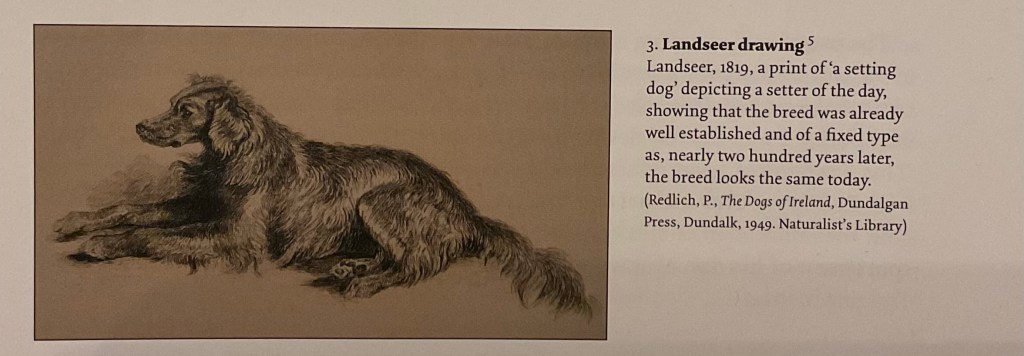

The fixing of type was well advanced in the early nineteenth century, exemplified by the Landseer etching of an Irish Setter of 1819, which shows an animal little different from the working setter of today. In the days prior to commencement of field-trials and shows, strains of setters were held by different families for their own pleasure. Setters were bred on a purely functional basis, as the dogs were kept for work. Indeed, the fixing of type and colour was achieved before the advent of these events and, more importantly, before driven game became the fashion. As a result dogs were bred for their ability in the field and their ability to withstand the Irish terrain and climate.

The practice of shooting birds on the wing only came into vogue in the latter half of the eighteenth century, prior to which dogs were used for hawking or for locating birds to be netted. With the development of the shotgun and subsequent interest in shooting came the real development of setters required to find game for the gun. From the time of King William III to the unfortunate rising of 1798 rural Ireland was the fairest field in the civilized world for manly sport, and the inhabitants, rich and poor, were as they are to-day – keen and the best of sportsmen. What wonder that their charming shooting companion, the red spaniel, should have prospered under such favorable conditions, and acquired his master’s rollicking love of sport, gradually developed into one of the best of sporting dogs.

(Credit- Raymond O’Dwyer , The Irish Red Setter Its History Character and Training)